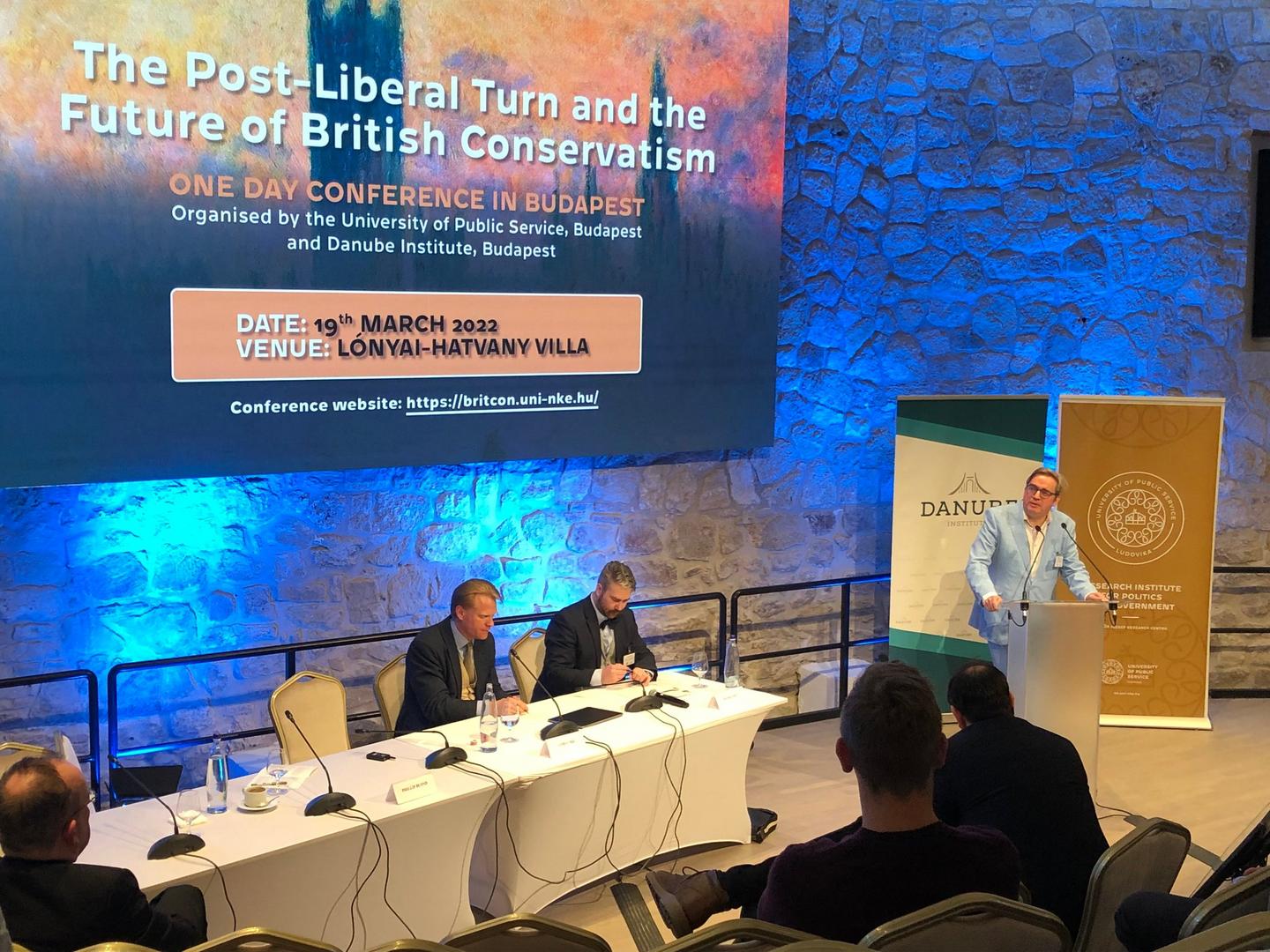

On the 19th of March 2022, the University of Public Service and the Danube Institute held an English-language conference at the Lónyay‒Hatvany Villa in Buda’s Castle District under the title „The Post-Liberal Turn and the Future of British Conservatism”.

The conference started with opening talks by leading representants of the organizing institutions. Prof. Gergely Deli, Rector of the University of Public Service started the conference with the quote: „Only those who change will remain true to themselves”, and pointed out that conservatism is not limited to preserving the values of the past, conservatives do not reject change, but they follow naturally developed historical frameworks, and do not try to enforce ideological constructs on society. According to Prof. Deli, the University of Public Service has a double mission of loyalty to proven values and the will to learn and adapt to arising new challenges.

Phillip Blond, director of ResPublica and visiting professor of the University of Public Service, whom the idea of the conference came from, stressed the end of liberalism as an uncontested hegemonic political philosophy. As by 2010 it became clear, that economic liberalism puts too much burden on ordinary working-class people and serves only the elites. Post-Liberalism tries to return to the liberty that liberalism has denied in practice. It can learn from the success of the „unorthodox” economic policies of the Polish and Hungarian governments, but according to Blond, all successful politics are universal, and nationalism only seeks the good of just one ethnic group, nation, or country, and post-liberalism would fail, if it cannot give a successful Christian-based universalist answer to globalist liberalism.

Prof. Ferenc Hörcher, research professor and director of the Research Institute for Politics and Government at the University of Public Service reminded participants of the architectural heritage of the „golden age” of Hungarian politics from the times of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy, and the British inspiration behind the building of the Hungarian Parliament. He also pointed out the similarities between the British and Hungarian ancient constitutions, and stressed the Anglophilia of Hungarian constitutional elites from Széchenyi to István Bethlen, and spoke about his personal ties to this tradition, also highlighting the raised stakes of research on British conservatism in light of the current Russian-Ukrainian military conflict.

John O’Sullivan, president of the Danube Institute shared his personal interest in wanting to find out what post-liberalism is. He stressed the importance of the preservation of the liberal values of society that came under attack by the progressive Left, as even one of the most important basic values of classical liberalism, the freedom of speech has become a contested issue. He also discussed the relation between society and economy, and the moral value of the concept of nation. He highlighted the importance of unchosen obligations in preserving society, since only those who accept these, can expect help from other people.

The first session of the conference (Liberalism and conservatism, repudiation or incorporation?) was chaired by Ferenc Hörcher, and discussed the relationship between the paradigms of liberalism and conservatism.

The first speaker was Dr. Christopher Fear from the University of Hull, who analysed the ‘two faces’ of conservatism, represented by the politics of the British Conservative Party. Michael Oakeshott called these two faces of conservatism ‘scepticism’ and ‘faith’. Conservative politics of scepticism is based on the idea of prudence, while the politics of faith is centred upon the success criteria of a human life within established institutions, focusing on personal advancement and eudaimonia. The Conservative Party should keep its scepticism towards the egalitarian politics of faith and focus on the common good of society. Conservatism is inegalitarian, as there are natural differences between people, and the common good of society requires a meritocratic ranking. It cares about loyalty, authority and sanctity, not just about liberty and equality. The Conservative Party has an electoral advantage over liberals and socialists because of the idea of a successful life, and it will continue to succeed as long it understands how to develop a coherent programme of restoring the real institutions of personal advancement as a means to fortifying its new working-class support base.

The lecture of Kit Kowol (King’s College London) was focusing on the lessons from the Second World War regarding the ideological conflict between conservatism and liberalism. He examined the historical role of the Central Committee for National Policy, founded by R. A. Butler in January 1940, that aimed to propose a programme for a postwar new England, based on conservative and national values. Butler recruited prominent political thinkers like Edward (Max) Nicholson, Oliver Franks, William Weir, and Hungarian-born sociologist Karl Mannheim. CCNP wanted to combine a new authoritarian element with the ancient liberties, they put a strong emphasis on developing a sense of national obligation and Christian values in the individual citizen in their Educational Aims (September 1942), and also presented A Plan for the Youth proposing organizations that give opportunity for younger generations for the service of the state, individual training and collective discipline. Some of these proposed policies came to life in state-sponsored programmes of youth development, that promoted loyalty towards the state through the respect towards the environment and studying national history.

Dr. Kevin Hickson (University of Liverpool) examined the past, present, and future of the British Conservative Right. Since the 1970s the right-wing of the Conservative Party has been synonymous with free-market economics, but this has created a lot of problems, as it was contrary to some core conservative values, and Tories had been sceptical of free-market ideas in the past. Thatcherism undermined conservative values and created new rich classes destroying the agents of traditional Britain. The contemporary, post-liberal conservative positions are showing elements of national interests and an anti-modern approach, promoting a stronger sense of Englishness.

The panel ended with a vivid open discussion on the topics of social and economic liberalism, classical versus new liberalism, the evaluation of Thatcherism, and the lessons of Brexit.

The second session, chaired by Phillip Blond also featured three presentations regarding the living and dead traditions of British conservatism. Dr. Matt Beech (University of Hull) discussed the conservative traditions in the age of Brexit. According to him, the Conservative Party incorporates a plurality of traditions, it is open to new impulses outside of the party, and a living conservative tradition can often be found outside the Conservative Party, too. Countless millions of working-class Labour voters wanted to leave the cosmopolitan project of the EU, and the issue of leave or remain still dominates British political discourse years after the referendum, and it is only the top of the iceberg. The willingness to reclaim sovereignty enabled Boris Johnson a comfortable majority government, and signals a cultural realignment in British politics. The late Sir Roger Scruton pointed out that democracies owe their existence to national loyalties shared by government, opposition, and all political parties. According to Beech, liberalism is the mother political ideology, both socialism and conservatism derive from it. He considers classical liberalism a noble tradition, deriving from Christianity. Without liberalism, there is no recognition of individual rights of freedom. The post-liberal agenda arises from the corruption of contemporary liberalism by different forms of Marxism beefed up by the French postmodernism of Foucault, Derrida and Lyotard. This extreme individualism and relativism is not the same as the respect of the innate value of every individual in union with the traditional communities, the backdrop of conservatism.

Dr. David Jeffery (University of Liverpool) examined the evidence of the post-liberal turn in British conservatism by analysing the extent to which post-liberalism can be found within the modern British Conservative Party both in terms of the parliamentary party and among the party’s voters. At the beginning of his talk, Jeffery characterised what he understands under post-liberalism by making out four points. He then went on to analyse the speeches of all candidates of the 2019 Conservative Party leadership election, and eventually stated that the close reading of these speeches does not even really show a glimpse of postliberal support, as these were essentially liberal in outlook. Jeffery also analysed with the help of empirical data the elements of post-liberal thought in the preferences of conservative voters, building up a scale that makes it possible to measure the post-liberalism of voters of each party. According to the result of his analysis, post-liberal values are unsurprisingly more widely held among Conservative voters than Labour voters, but those Conservative post-liberal voters were not well represented among the party’s leadership contenders, and therefore, it remains a future task to bring party lines to meet the post-liberal attitudes of their voters.

Daniel Pitt, an external research fellow of the Research Institute for Politics and Government at the University of Public Service talked about a conservative, post-liberal view of the environment, centred around the Greek notion of oikophilia, the love of home. In his presentation, he argued that conservative environmentalism is different from liberal and ‘woke’ positions, drawing on a conservative environmental tradition represented by Edmund Burke, William Wordsworth, Roger Scruton, Wendell Berry and Adrian Vermeule. According to Pitt, the post-liberal conservative view of environmentalism is based on seven core principles: Oikophilia, trusteeship, localism, intergenerational obligations, piety, embeddedness and prudence. This living tradition can lead to a coherent governing philosophy triggering a clean and green bundle of policies of sustainability.

The session finished with the response of well-known English historian and journalist Andrew Roberts (King’s College London and Stanford University), who reflected on the key issues raised by the three speakers of the panel, and he also shared some personal experiences regarding some important political thinkers and practical politicians of past and present.

he third session was chaired by Daniel Pitt, and put post-liberal conservative perspectives and principles under scrutiny. It started with the online presentation of Prof. Eric Kaufmann (University of London), who highlighted the importance of classical liberal basic values for conservatism, and raised awareness for the contemporary cultural emergency situation, that is a result of the institutionalized anti-conservatism in high culture, making it absolutely necessary for conservatives to shift their focus from secondary economic issues to culture. There is a strong need to resist censorship and cancel culture and stand up for freedom together with classical liberals. Cultural liberal and cultural socialist worldviews are affecting younger generations, making them deeply prejudiced against free speech and academic freedom. This threat of liberty is coming from activists, who are trying to create a deeply intolerant culture that has nothing to do with liberalism. Deeply illiberal progressive activists restrict free speech, and worship historically marginalized identity groups as totems. This wokeness is rooted in the 1960s, when cultural socialist intellectuals turned against their own ethnic groups, promoting a non-tolerance for conservative ideas, embracing multicultural diversity, and urging minorities not to assimilate. The biggest problem is that conservative political leaders are shying away from a campaign on these cultural war issues. Governments should overwrite the will of universities and kangaroo-courts, as liberty of individuals is more important than the liberty of institutions. Universities should not be allowed to impose woke statements on employees. Political belief should be a protected characteristic of every individual. Negative liberty, shared by both classical liberals and conservatives, is a more important value than a claimed challenge to equity and diversity.

Dr. James Orr (University of Cambridge) discussed the relation of Christianity and post-liberalism, and stressed the importance of metaphysics in both the British conservative and even the Lockean liberal traditions. Christian metaphysics also play a key role in contemporary post-liberal political visions as well. John Rawls tried to eliminate any conception of the ‘Good’ from the philosophy of justice, but it does not seem to be possible to think about a just society without the concept of the common good. Metaphysics only works if it is religiously charged, hyper-progressivism is an extremist mutation of Christianity. It is based on the metaphysical conflict of good and evil, and salvation can be attained by deconstructing the entire institutional landscape of Western society. Only the state has the power to intervene, otherwise this would go on until the complete disintegration of the public order. A theologically grounded post-liberalism is needed to save liberalism from itself, focusing on the common good through a more substantial view of freedom and of human nature.

Phillip Blond started his speech by reflecting on the current Ukraine-conflict, expressing his rejection of nationalism, that, according to him, inevitably results in wars between nation-states. In his view, the good is imperial and universal. Therefore, post-liberalism should be universal, based on Christian values, that emerge from Judaism. For Blond, liberalism and woke culture are one and the same, as there is no objective good in liberalism. Only empires can produce toleration. There is a need to differentiate between good and bad empires. Closed, ethnic-based empires like Russia or Nazi Germany are bad, the post-liberal project should be realized within the framework of an open empire, following the historical example of the most inclusive, open empire, which was the Roman Empire. According to Blond, there is no alternative, the post-liberal civilisational project must have the characteristics of a good empire.

The fourth and final session of the conference featured a debate on the challenges of post-modernity moderated by Phillip Blond. The participants of the discussion were British conservative MP Danny Kruger, and John O’Sullivan, president of the Danube Institute. Kruger pointed to the Christian origins of the idea of the unique value of the individual, and discussed the issues of liberalism going wrong, the governments’ responses to the COVID-crisis, the reinforced globalism in response to the Russian aggression against the Ukraine, and the skirmishes of culture war. He also stressed the importance of giving young people an opportunity for activism in a constructive mission to build.

John O’Sullivan reflected on the aforementioned issues like the notion of empire and nation-state, and the origins of post-liberalism. He contested Blond on the necessity of empires, and pointed to the different situations behind the emergence of historical states and empires. According to O’Sullivan, the British Empire could successfully transform into nation-states, meanwhile the EU can be viewed as a transnational polity tending towards an empire, and this is incompatible with democracy, as democracy does need a nation-state, probably with an ethnic majority. He also reflected on the policies of Margaret Thatcher’s government, and on how gender theory affects the relations between men and women, arguing in favour of a realistic and decent feminism, that would not make it impossible for men and women to get together and stay together for the future of the world.

The conference finished with an open discussion, involving the topics of the clash between civilizations, the risks younger generations are facing with extensive online presence, the role of civil society in politics, the role of the state to underpin culture, and on the possibility of a post-liberal Christian revival. In his closing words, Phillip Blond once again argued that only universalism can defend difference.

The conference gave room for various political and philosophical approaches to the phenomenon of post-liberalism, highlighting its complex nature and ongoing development. The two main issues, on which the lecturers presented contrasting views, were the relation between classical liberalism and contemporary ‘woke’ progressivism, and empires versus nation-states. Attendees of the conference witnessed a lively intellectual event of very high academic quality that gave specific answers and raised further questions on the relation between conservatism and post-liberalism, and on the meaning of these notions, signalling an important milestone in the ongoing discourse of contemporary political thinking.

Kálmán Tóth

junior researcher

UPS JERC Research Institute for Politics and Government