The workshop, organised by Ferenc Hörcher (Institute of Philosophy of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Research Institute of Politics and Government at the József Eötvös Research Centre of the National University of Public Service) with the help of Ádám Smrcz and Kálmán Tóth, aimed to uncover the underground and grass root currents of post-Nazi German conservatism in the post-war political and intellectual milieu. Its aim was to uncover the long term causalities within the traditional German theory of state and politics, as well as of philosophy. Participants of the conference included historians of political thought, legal scholars, historians and philosophers, all joining a lively discussion which aimed to uncover an until now mostly hidden intellectual trajectory within German political and intellectual life. It attempted to raise interesting and confront contestable questions about key players in post-war German conservatism in politics and in the intellectual field.

After the opening remarks by conference director Ferenc Hörcher, the conference started with Günter Figal’s keynote lecture titled Tradition as an Event and as a Kind of Freedom. In his lecture, Prof. Figal elaborated how the key terms of Hans-Georg Gadamer's philosophical hermeneutics, Authority, Tradition, Understanding and Application – the former two labelled as conservative by Habermas in a negative sense – are not in contradiction with Freedom, which is regarded in the Western Tradition as a legitimating force of philosophy, since Gadamer’s concept was aiming to stress the importance of finding the right balance between common tradition and individual freedom. These two terms are not contradictory, the former making the latter possible, conservation making sense to a large part for the sake of liberating philosophy.

This philosophical introduction was followed by Wolfgang Fenske’s historical overview, whose introduction reflected on the history of conservative ideas along a timeline of four different periods and taking into account five criteria of conservative thinking. Participants of the conference were divided into three thematic panels, with the first discussing the influence of controversial, but surprisingly influential 20th century philosopher, jurist and political thinker Carl Schmitt. Relying on archival materials, Samuel Garrett Zeitlin and Joshua Smeltzer both stressed the fact that there was no significant rupture in Schmitt’s thought after 1945. According to the speakers, he never distanced himself from his national socialist past, and the content of his teaching was not conservative, either, only antimodernist. Attila Gyulai was focusing on the reception and contexts of Schmitt’s post-war anti-liberalism as a fountain head of a new trend of realist understanding of politics.

The second panel was focusing on legal thoughts and thoughts on government, with Clara Maier examining the theoretical and political aspects of the foundation of the Bonn Republic – the West-German Rechtsstaat that has been built on the existence of basic human rights as pre-political principles – and its relation to the Sozialstaat, that is also layed down in the Constitution (Grundgesetz) and its early official interpretation. She also outlined the criticism that emphasized that the focus on the Rechtsstaat pushed the constitutionally also demanded social state in the background. Conference director Ferenc Hörcher’s lecture, “Transcending the functional ‒ Conservative Intimations of the Böckenförde Dilemma” outlined the complex rapports of Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde’s famous dilemma formulated in 1976 on the inability of a liberal democratic state to guarantee its own prerequisites without losing its liberal character. Hörcher emphasized that Böckenförde was aware of the need to transcend value relativism, paying special attention to the role of non-state institutions such as churches in sustaining the ethical foundations of the state within the relatively homogenous community of citizens. In Böckenförde’s view this foundation is fragile, but nevertheless a necessary thing for the state.

The third and final panel discussed the philosophical aspects related to conservatism, mainly the criticism of modernity in the thinking of Joachim Ritter and in the works of the members of his school. Csaba Olay examined the theoretical pillars of Ritter’s conservative-liberal position, with special attention to his student’s, Odo Marquardt’s thought, who elaborated an anthropology and political philosophy of finitude that embraced Ritter’s analysis of modernity, but radicalized certain points of it. Péter Varga investigated the intellectual trajectory of the philosophical achievements of Catholic thinker Robert Spaemann, one of Ritter’s first students, who belonged to the group known as the “Ritterian Middle”. The final lecture of the conference, held by Kai Graef, gave an overview of Reinhart Koselleck’s conservative critique of the philosophy of history, focusing on Koselleck’s famous work Critic and Crisis (Kritik und Krise) by embedding it into the context of works written by Koselleck’s teacher in Heidelberg, Johannes Kühn and his fellow students in Heidelberg, Nicolaus Sombart and Hanno Kesting. Members of this group shared the view that the crisis of European history had begun with the French Revolution in 1789 and resulted in a sense of global crisis, which led to the birth of 20th century Totalitarian regimes.

The conference was finished by a roundtable discussion, in which plans were proposed to publish a book on the topic of the conference by 2021, based on the papers presented in Budapest.

Kálmán Tóth

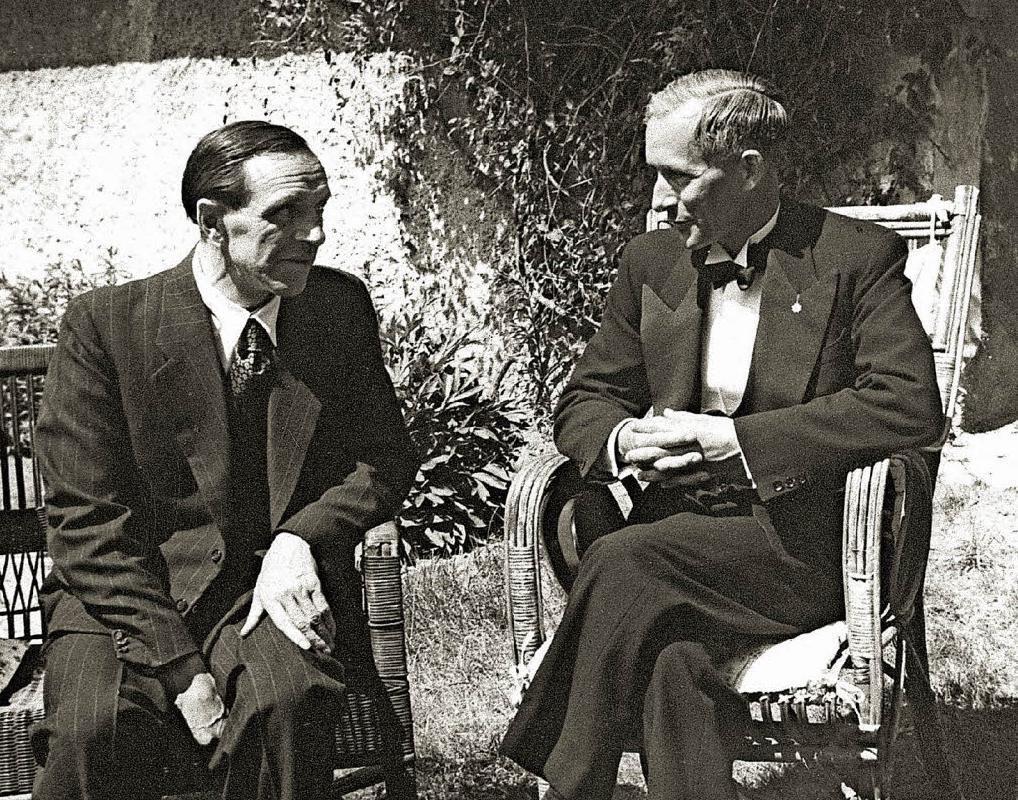

Carl Schmitt and Ernst Jünger

Source: Pinterest.cl